An undergraduate drawing assignment, which kicks off an interdisciplinary studio course exploring visual language and meaning.

It can be useful to think of visual images as text-like, in that we may “read” them. Our challenge in this assignment is to create a self-portrait using inanimate objects that when gathered together might convey ideas about you; a symbolic self-portrait. How might we create a visual vocabulary of images, symbols, and signs, that individually and/or collectively convey meaning?

Part 1. Gathering your source material

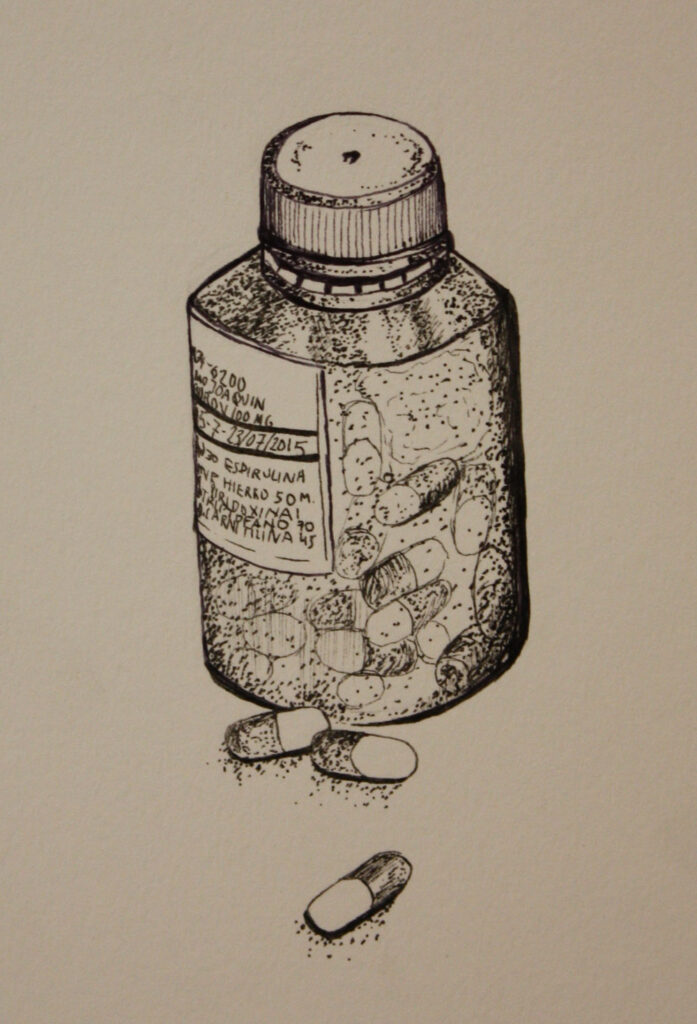

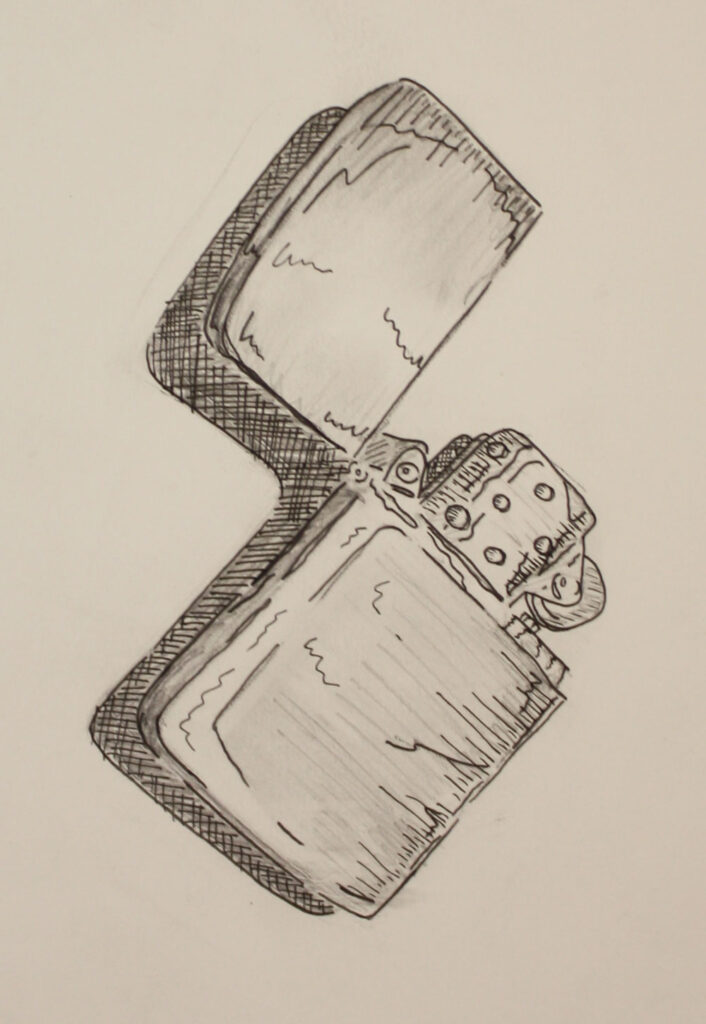

Collect 10 items; objects that are meaningful to you. Consider how they tell a story about you, your life, your values, beliefs and your personality. Consider the kind of stories that you associate with each object. Your collection of 10 items should provide a rich narrative that tells us something about you.

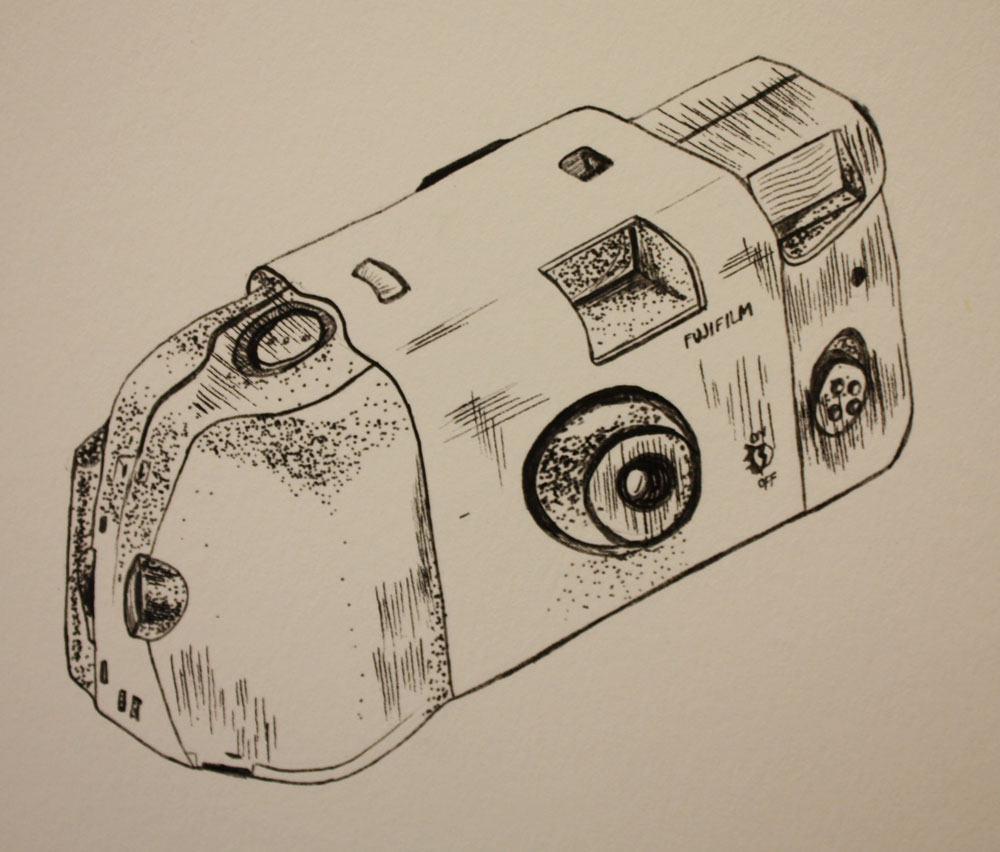

Draw each of the ten items.

One drawing of each item in pencil; each drawing on one half sheet of white Bristol paper. 9 x 12″

Part 2. Moving from image to idea

Create an information map of all of the items, transforming each item into a graphic symbol (a pictograph) and pairing each item with text.

- Write a short (no more than three or four sentences) story about each object.

The stories might address any number of themes. For example. They may tell the story of how you attained the object, its cultural or sentimental history, its form, or socio-political references; it may be focused on the value such as cost, or time that you’ve had the item. Consider a general theme that you use to approach your stories.

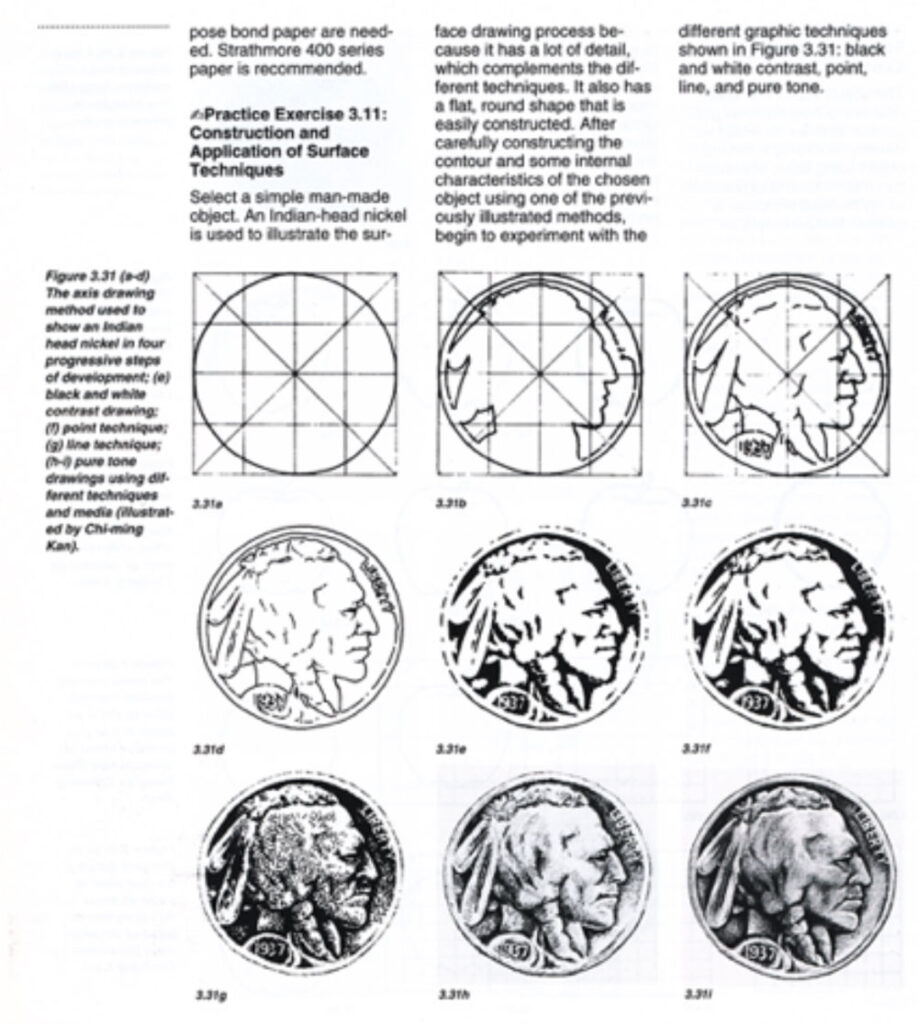

One useful model is to look at each object through a thematic lens and then tell the story(ies) from one or more of those perspectives. For example if we look at this 1929 five cent nickel coin from the United States of America we may at first see a coin, but what ideas might we perceive if we look again at this nickel through a particular context.

Next Steps

- Photograph each object, save as a tiff or jpeg

- Draw each object in pencil, pen, or other media, in several different ways. Scan the artwork into the computer.

- Open the scanned art work in Adobe Illustrator and using the pen tool, live trace, or other techniques create black and white symbols in Adobe Illustrator based on the photos and drawn images. Note use a grid to organize your symbols. Your goal is to create a common visual language for your pictograms that will be recognizable across all of your objects.

Drawing Techniques

A note about Semiotics

“Semiotics is concerned with meaning; how representation, in the broad sense (language, images, objects) generates meanings or the processes by which we comprehend or attribute meaning. For visual images, or visual and material culture more generally, semiotics is an inquiry that is wider than the study of symbolism and the use of semiotic analysis challenges concepts such as naturalism and realism (the notion that images or objects can objectively depict something) and intentionality (the notion that the meaning of images or objects is produced by the person who created it). Furthermore, semiotics can offer a useful perspective on formalist analysis (the notion that meaning is of secondary importance to the relationships of the individual elements of an image or object). Semiotic analysis, in effect, acknowledges the variable relationship[s] we may have to representation and therefore images or objects are understood as dynamic; that is, the significance of images or objects is not understood as a one-way process from image or object to the individual but the result of complex inter-relationships between the individual, the image or object and other factors such as culture and society.

Given the root of ‘representation’ in notions of resemblance and imitation, among other factors, visual images have often been thought of as more direct and straightforward in their meaning than language itself, which varies from culture to culture. Or, in other words, there has been a strong tendency to think of visual images as not a language, as un-coded and possibly universal in their meaning. Furthermore, as a result of a pervasive link between visual art and the idea of expression, art has been thought of as more intuitive, unconscious and basic than language; therefore transcending the specifics of the culture[s] it emerges from. This, of course, is not true.”1

Next Steps

- Using the stories and the pictographs design an information map that maps out these objects and text to provide a forensic description of you.

- Colors: Black, White, Gradients and optionally one additional color

- Size: Minimum 18 x 20″

- Typography: Up to two typefaces

- Use an organizational structure for your design.

e.g. Modular Grid, Symmetry, Asymmetry, Rotational, Bi-lateral, vertical, horizontal, etc. Refer to the Gestalt Principles of visual organization which you learned about in Design 1, 2 and 3.

Deliverables Due

- Part 1 due week 2

- Part 2 drawings and symbols due week 3

- Final due week 4

Materials

- Portable hard drive or a thumb drive to store digital images

- Digital camera. If you don’t own one, you may borrow one from the equipment center on the top floor of Arnold Hall 55 West 13th Street.

- Pencil

- Ruler

- Technical Pen

- Bristol Paper

- Tracing Paper

- Large pad of white 3- or 4-ply smooth finish paper

- tracing paper, pad or roll

- white art tape

- Pushpins (for tacking work to walls in class)

- Sketchbook. 1 Canson 180 Degree Hardbound Sketchbook 80 sheets, 8.3″ x 11.7″

- Strathmore 300 Series Drawing pad, 18″ x 24″

Examples

Drawings of objects found in Alfred Hitchcok’s cinematic murder scenes by visual artist Martín Sichetti

Selected student sketches

Addendum

Project Notes2

The forensic “proof” is arranged on a “canvas”. Sketching an image of the maker, which must in turn be read and identified by outside parties, in this case the other students. They are the detectives who have to reconstruct an identity on the basis of the available clues. Those providing the clues have written down in advance how they think they will be perceived, but will the story be interpreted the way they expected? How great is the gap between intent and interpretation?

The forensic self-portrait in which a personality is sketched through image, text and sign, touch the very core of the graphic design profession. They raise questions about how we decipher the signs and characters that serve as glossaries, symbols or icons. They demonstrate how every communication is subject to several interpretations and that the designer is able to manipulate that perception when he is capable of making the leap between his own perceptions and those of the viewer.

Identities

The design bears the signature of the designer. The designer is an author. On the other hand, s/he derives their self-image from the efficacy with which s/he interprets the desired self-image of their client for a more or less given public. The designer interprets and reinforces someone else’s story. The modern designer therefore determines themselves, but is determined by others as well.

- Curtin, Brian. Semiotics and Visual Representation, International Program in Design and Architecture

- This assignment has been adapted by Prof. Andrew Robinson from the Forensic Self Portrait project, Copy Proof: A New Method for Design and Education, edited by Edith Gruson, Gert Staal, 010 Publishers, 2000.

More information from the original project, and student examples of gathering artifacts can be seen on pp 20 – 39.